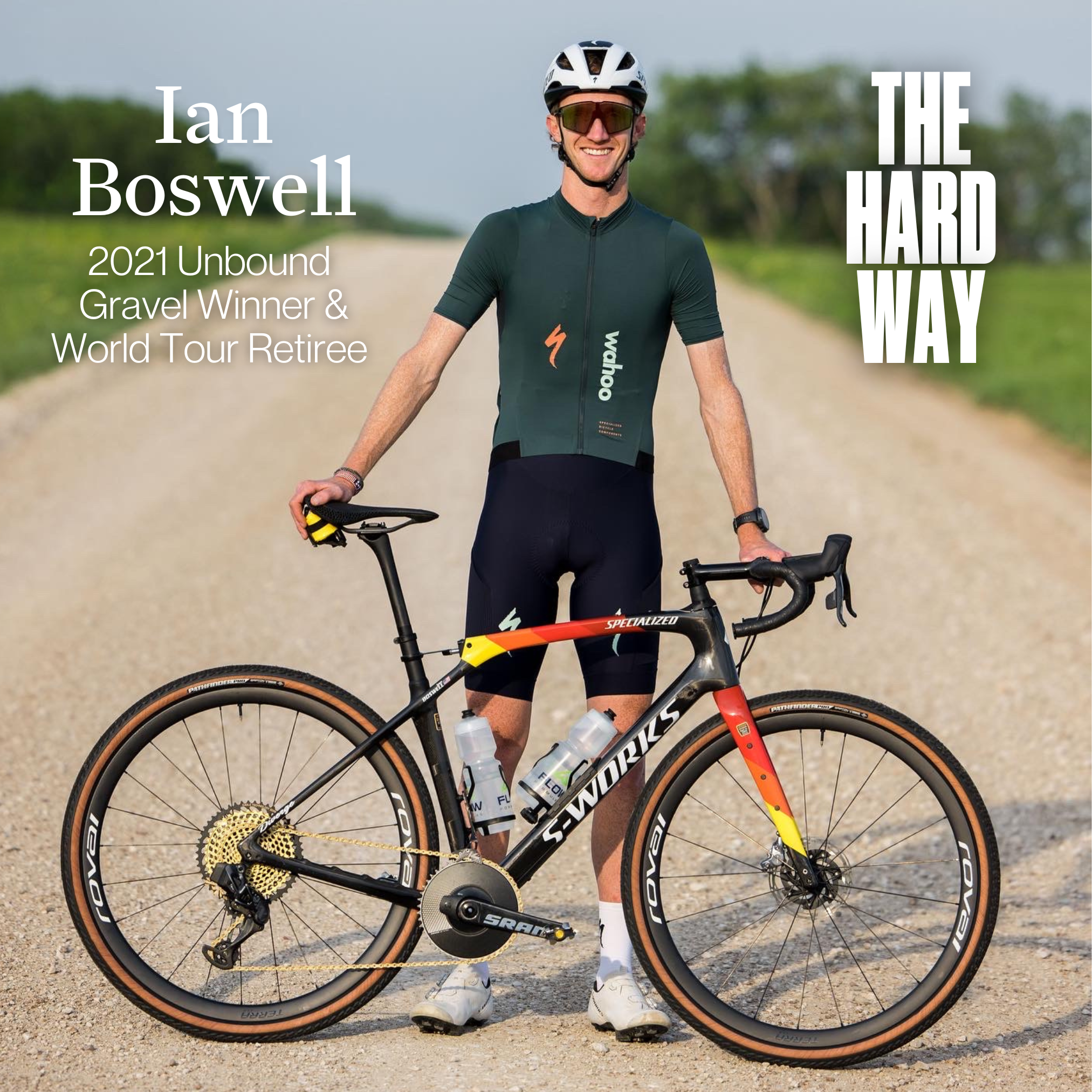

Ian Boswell: 2021 Unbound Gravel Champion, Retired World Tour Pro Cyclist on Competition, Balance, Starting Over and the Past, Present & Future of Gravel

LISTEN NOW: Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music, YouTube, Google Podcasts, Stitcher

After being forced to retire from professional cycling due to a series of concussions, Ian Boswell could have easily slipped into obscurity. Instead, he reinvented himself as a dominant force in the new world of gravel racing - and he's not looking back.

But it's not just about winning for Boswell. He's focused on balancing family life, homesteading, and a full-time job at the fitness tech company, Wahoo. He sat down with host Andrew Vontz, to discuss his path to success, the challenges he's overcome, and the future of gravel racing.

The 2021 Unbound Gravel champion was formerly a member of Team Sky, the world's top pro cycling team, where he competed in all three grand tours of Europe - the Giro, the Vuelta, and the Tour de France. Alongside his current race schedule, he hosts a podcast called Breakfast with Boz, featuring interviews and news from inside the industry.

LISTEN NOW: Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music, YouTube, Google Podcasts, Stitcher

Choose the Hard Way is a podcast where guests share stories about how hard things build stronger humans. Sign up for the newsletter to get the story behind these stories updates and more. If you’d like to suggest a guest or say hello, DM @hardwaypod on social or send an email to choosethehardway@gmail.com.

Host Andrew Vontz has spent more than 25 years telling and shaping the stories of the world’s top performers, brands and businesses. He has held executive and senior leadership roles at the social network for athletes Strava and the human performance company TRX. His byline has appeared in outlets like Rolling Stone, Outside magazine, The Los Angeles Times and more.

Today he advises and consults with businesses and nonprofits on high-impact storytelling strategies and coaches leaders to become high-performance communicators. Find him on LinkedIn or reach out to choosethehardway@gmail.com

In This Episode:

Ian Boswell Instagram

Breakfast with Boz Podcast

- - - - - - - - - -

Andrew Vontz LinkedIn

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, Stitcher

Sign up for the Hard Way Newsletter

Choose The Hard Way is a Palm Tree Pod Co. production

-

Andrew Vontz 0:00

Great. Yeah, that's what I like to hear. Yeah, fantastic. So, I know you've been on Anthony's podcast before. Thanks for taking time to do this one. I don't know if you've had a chance to listen to it or not. But I focus on how hard things build stronger humans, and more importantly, how doing hard things is generally the most fun and most rewarding part of life, whether you choose those things or not. And, you know, I'm very familiar with you in your career. My show is not always about cycling, but it's been about cycling quite a bit recently. My background is I was the Vice President of Communications at Strava, I helped grow the community to 100 million users to a profitable business. I was there seven years before that I was the head of content at TRX, the human performance and training company. And before that I was a journalist for a decade, for outlets like Rolling Stone Outside magazine, or I did a lot of stuff for the different cycling magazines. But again, that wasn't really the primary focus of what I did. And I've been involved in cycling on bikes with gears for probably about 35 years now. It's always been an important part of my life. I got started in 88. And yeah, I was always, always pretty mediocre. I did get second at the unbound 100 twice. So I've been a loser a couple of times there. But that was before, you know, before the hitters really showed up. So that's

Ian Boswell 1:28

my only racing against people that show up. So yeah, I love it. Yeah,

Andrew Vontz 1:33

I love it. There we go. Anyway, and I've got a four year old and a six year old. I'm actually I'm in Haute, Maine. So I'm just to the east of you. I was standing I think within four feet of you at rescue T TSA, congratulations, you beat me by about an hour. And yeah, and yeah, so that's like a bit about me and the show. And we'll just, you know, I've know you've done a gazillion podcasts, we're just gonna chat. My listeners really tend to love stories, that clearly there are dozens and dozens of podcasts and this kind of space, a lot of them focus on here are five things you can do blah, blah, blah, what I found is for listeners, that's usually kind of in one year, one ear and out the other, but they really value getting to know people like you a little bit better hearing stories from you, and, and all of that. And the last thing that I would share is, and then this really long monologue is gonna stop and, and we can talk about heat pumps, because I've got one in my space as well. Oh, yeah, yeah. Yeah, yeah. The other thing I'm doing now is I'm starting a tech company with another former Strava executive. And I've been doing that for about eight months. So I'm getting my dose of trying to do hard things every day outside of out of work in life.

Ian Boswell 2:49

What's the tech company?

Andrew Vontz 2:53

Just super broadly, it's focused on helping people build simple habits to feel better and improve their health.

Ian Boswell 3:00

Okay, very cool. Yeah, we'll need that.

Andrew Vontz 3:02

Definitely do. Do you have any questions before we just kind of started kicking up, man?

Ian Boswell 3:08

No, whatever, whatever you got to answer I'm willing to try the best to. Yeah, share my stories and perspective on

Andrew Vontz 3:17

Okay, awesome. Why don't you tell me a little bit about your experience running in mud? How good are you?

Ian Boswell 3:24

I am not that great at mud run into mud. Actually. I really hate mud. Yeah, I grew up in Bend Oregon, which is like high desert. You know, it's like we get you know, it goes I was just out there recently for a race. And it goes straight from like snow to sand. You know, it's like growing up. I never wrote in mud. I like wouldn't train in the rain. I live in New England now. So mud is more prominent, I guess if you're going to be a cyclist, but even then I like if it's like during mud season like I don't ride my bike rest petite. So thankfully, the two years I've done it. And then I guess we're both next to each other at the start line. You know, it doesn't seem like mud season really happens in New England at the end of April anymore. I guess I just really enjoy keeping my equipment clean and in working order. So I really avoid it at all costs. But this year at Unbound, we did have mud, which is kind of surprised that I did well, considering me. We had those conditions. But I think it was more about how I approached the mud over my skills in the mud.

Andrew Vontz 4:23

Well, that's kind of what this show is about. What are the skills that you take when you approach the mud that you might step into in life or work or whatever, right? So when you when you hit the mud, you probably knew that was coming based on your pre ride the day before or an intelligence you'd gathered, I would guess so what was your strategy going into it?

Ian Boswell 4:41

Yeah, I mean, I knew this section was coming. You know, I over the course of my sporting career, I have learned for me it works to not really see these technical sections. You know, in 2018 I did the Tour de France and we did this like parry rebase section over the cobblestones and we well, I didn't make the choice but the team won To go recon the stage after Liege Bastogne the age, which was a horrible idea because I had never written the cobbles every day. I knew I didn't, I wasn't going to win the race, I was just there to like, get through that stage because, you know, we had a rough day and then we're in the Alps, which was kind of my time to do work for the team. And I learned there that for me, seeing something ahead of time makes it worse. Because then you start to think about it, you think you start to like overthink all these little details that you've already made a decision in your mind. You know, when I left Vermont on Wednesday, before Unbound, I knew that like I was going to run into the tires, I was going to ride. I already made those decisions. So to get to Unbound, I didn't ride that section. I don't wanna say intentionally, but again, I don't like getting my bike dirty like it, seen it beforehand going to help anything or is it just gonna make me worry more stress more, you know, make me like, oh, the night before I was over at the specialized team house, and they're all swapping tires, and they've gone from a 47 to a 42. And then they're like, oh, she'd run a 38 tire. They're asking me I'm like, You know what, I already made this decision weeks ago of which tire I'm writing. It's on my bike. Even though we had mechanics there. I was like, I'm not going to. I guess one thing I really love about gravel is I try to do as much as I can myself, you know, I don't even mounted my own tires, put the sealant in. If something goes wrong, I want it to be my fault, not someone else's fault. Like, oh, that mechanic didn't you know, do this, right. It's like, I want it to be my responsibility. So I didn't recon that section. I knew it was coming. I'd seen some pictures. But the way I approached it, and I think the way I've approached unbound the three years I've done it now is it's such a long event, you know, it's 200 miles, it's anywhere from you know, I guess last year was nine hour or something this year was was 10 hour or something. There's so much time to make up for small mistakes, but big mistakes can really take you out of the race, you know, so we hit this we came into this midsection. I was near the front before it. But all these people who are so eager to win the race and their goal is to win, you know, they just went treaded straight up the middle of this muddy road. And within you know, 200 yards, they were at a standstill running to the side of the road. Meanwhile, I was a little bit further back, you know, still near the front, but I saw a writer who I know fairly well John karaoke from Kenya on the team Amani, and he's a really smart and savvy writer. And I saw him go left onto the grass. And I was like, this kid is smart, I'm gonna follow him. And also the benefit of having someone on the grass is that you can come in up. So I was able to follow him up the side of the grass and there were times that we had to run and, you know, for the first time in my life, I had carried up a paint stick in my pocket, just to get mud out. That was something I didn't I did practice the night before I went took the paint stick to Freddy's frozen custard and ate some frozen custard with the paint stick but that was that was pretty much it. I guess that's kind of been my approach to unbound over the last couple of years is just playing the long game but letting other people make those mistakes before I make the mistakes

Andrew Vontz 8:15

How did the paint stick take off the last year I did? Dot unbound 100. In the last time I was important Emporio racing, I believe it was 2015 and at that time, Chris I actually I ran into Chris Carmichael the night before the race and his recommendation to me was just carry a small flathead screwdriver, which is what I ended up taking with me. I did need it because like you we ran into this horrible mud bog situation. I think for us it was about an hour end of the race. I did end up having to run for about 45 minutes. I did make the mistake. I made the mistake of writing directly into it. I you know, I've done a lot of cyclocross. It's like I can handle this I got totally packed down. And then it was like a battle scene from Game of Thrones for the next 45 minutes and every time I'd crest a hill I was like it's got to stop and then you just see another 500 People from the 200 Pushing bikes removing derailleurs it was just carnage but how did the paint stick take off because everybody had one tape to their bike this year?

Ian Boswell 9:21

Yeah, well, I think the first year I went in 21 I think they actually handed them out in your bag in like your you get go get your erasing them when you get a little swag bag with you know, some chain lube and a koozie and a sticker. And there was a paint stick in there and that was the second ever gravel race. I didn't 2021 I was like, do they have is like Sherman Williams, a sponsor of the race. I don't know why this is any of this. I just I had never done cyclocross. I've never done a big gravel race. I didn't know what it was for. This year. They did not put them in the bags. But I guess it's just it really is like the optimal tool for it's unlike a screwdriver. It's not going to kill you. If you crash on it. You know, you're gonna punch or kidney, if you have a screwdriver in your pocket. You know, it's like they're super cheap. You know, I actually like cut mine down the place we're staying. There's little hacks on the garage like took a couple inches off, it fits, you know, I finished with it in my pocket. And I forgot about until I got back to the house to shower like, oh, I still have this in my pocket. And anyway, it's thin enough, you can put it between your you know, the crown of your fork and the wheel and it oddly enough, it's probably good for about two things during paint and getting money out of the bike.

Andrew Vontz 10:32

It sounds like you've actually created a shiv. knifelike implement used in prisons for violent attacks.

Ian Boswell 10:39

I actually did I actually even took it like once I was just messing around. Once I cut it off, there was like some little splinter. So I actually took it out on the concrete and actually, like, sharpened it up a little kind of just like a shame.

Andrew Vontz 10:48

Yeah. Yeah, totally. You never know when you're gonna need that. Well, that's interesting. So did you end up having to use your paint stick at all during the race? Or did it stay back in jersey pocket the entire time?

Ian Boswell 11:00

No, I use it quite a bit, especially in that first one of, you know, from mile 11 to 15 or something, oftentimes, while trying to like walk my bike and like, you know, mostly get it out in the foreground. You know, later on in the race, there was one point, probably like maybe mile 14 or 15, where I had it in my hand writing for like a full mile because I was like, Cool. I'm gonna keep it and like I was trying, I was trying to think as I was writing, I was like, cool, it's okay, if I try to push the mud out from the front, you know, front of the fork, because if if it gets caught, it's going to kick it back out. And I was like, about to put it in behind the fog, because it gets a bad idea. Because if this gets stuck in there, I'm just gonna go straight over the handlebars. So I was trying to do some mud clearance as I was riding, but for the most part, it was when I was either stopped or Yeah, trying to walk with my bike and or carry my bike while simultaneously, you know, scraping money out of mostly just to keep the wheels spinning everything else, you know, bikes these days are pretty robust. Everything else was operational outside of you know, you're not going to go too far with wheels that don't spin.

Andrew Vontz 12:04

And at that moment in time, as you described, you kind of don't like to over focus on what are the obstacles you might run into. In an event like this? You don't like to pre ride. Once you hit it, were you able to remain in a calm headspace?

Ian Boswell 12:19

Yeah, I mean, I guess, you know, there was a small group of writers who were just ahead of us, you know, you know, Keegan Swenson who went on to win and I was with Russell for a while. But you know, you people get so especially at events, people get so caught up in like, the energy of the event, and they're like, trying to slam through gears and they're getting frustrated, which never helps any situation. I mean, you were talking about you have a you know, a six year old kid at home, it's like, getting frustrated, doesn't help anyone. So I was with Lachlan Morton, actually, and like, we could see the group ahead of us. And I was like, Hey, man, let's just keep it calm, we're 14 miles into a 205 mile race, there is no rush, like, we need to make sure we keep them in sight, but we don't need to catch them in this midsection. Like, we have plenty of time and strength to catch them. And so almost using them as a, as a guide, like literally like just keeping our eye off the road, like, hey, let's let them make the mistakes, like I can see there on the grass up here on the right, and then they're running across the road, like a little chipmunks and they're over on the left running up the left side. So that must be the line because there was enough people up the road that were trying different, you know, approaches and different lines, let's let them make the mistakes. And then we can kind of follow their tracks. And that worked out really well. And you know, then once we got out of the mud in our bikes were, you know, almost a clean, but you know, workable, that's when we can then close the gap. And you know, that's when we can then try to like, catch back up to them. And it was amazing, you know, especially this year at unbound with the deepest field the races ever had to realize how much effort so many people had put into being on the start line, you know, not just the financial setup, but the training and the you know, equipment and mechanics and support staff. And after 15 Miles have a group of there's gonna be 10 of us, 12 of us. It's crazy. I mean, I liked it as much as I despise riding in mud I loved because it just immediately eliminated all the chaos of unbound. And it was just like a dedicated group of riders. And it's like, well, here we are, like, we survived. Let's just keep going.

Andrew Vontz 14:21

And then where was your head at for the rest of the race? Like once you caught that group, you get into a front group. What were you thinking as you rolled through the rest of those miles?

Ian Boswell 14:31

I mean, once we there was a front group of like, maybe there was six or seven writers. A couple of people had flats I caught back up with with Lachlan. John karaoke and Payson McKelvey was also with us. So we caught up and I immediately just went to the front started writing, you know, just knowing that hey, I knew the other writers in the group, you know, Keegan was there Russell was there. 10 Dan wasn't there and Pete standing or Peter back couch. We're not yet there. They caught us just after that. But I knew that this was such a good group. And and I know Keegan and Russell fairly well, I guess I also know their style of writing where they're just kind of like me in an idiotic way, they just want to ride hard. Like, they don't want to play games like, hey, let's just pull through and Reinhardt and that's exactly what happened. I knew if I started pulling through and like, right when I got to that group, they were going to understand, like, Hey, everyone, here's committed, you know, we've got a really strong group of riders, everyone's committed to, you know, first off opening a gap to the people behind us, you know, making sure that more riders aren't going to tag so we started, you know, kind of noodling around. It's pretty quick that, you know, that group could have swelled to, you know, 20 riders, 30 riders, 50 riders have we had we kind of took it easy long enough. And without really talking, it was pretty instant, where it's like, Hey, this is the group, this is the selection, let's ride. And, and we did that all the way until the first aid station, a couple of people had mechanicals and dropped off. Like I said, Pete Yeah, Pete sat down, Peter back off, and 10 Damn caught us. And that was like, That was a great addition to the group because those are also powerhouses that you don't want chasing behind. Because, you know, they will, they will catch you at some point, if they're not with you.

Andrew Vontz 16:10

Were there any moments that are sticking with you when you hit those next 180 miles or so.

Ian Boswell 16:18

And it's, I mean, you've done Unbound, it amazes me how quickly the event goes, you know, living in Vermont, the roads are always up, down, left, right. So you could do a five hour ride, and it goes pretty quickly. When you go do a training ride in Kansas, as beautiful as the Flint Hills are, it's kind of boring, you know, it's just cool, you're straight for 15 miles left turn straight for 20 miles, you know, it's a big, everything's just, you know, north, south, east west and big, long straight roads. But because the Flintstones are so notorious for flat tires, you're constantly focusing, you know, here in Fremont, you never flat you know, it's like you could like, you know, I can write the same tire for two seasons and not have a flat tire. But they're flat tires happen all the time. So you know, if we're in a paceline, and we have two people, and just because the nature of you know, cars push the bigger stones out of the way. So there's kind of two tracks, there's a bit thicker gravel in the middle. So as you're paceline, and you know, the people going forward will be in one lane, the people coming back will be in the other lane. You know, so eight riders, you're crossing over that center, you know, center patch, every 45 seconds, every minute, you know, twice, you're going in the front and in the back of the group. And I assume everyone in the group kind of thinks the same way, you're really looking, where can I cross this? You know, where's the safe spot to cross this? Can I cross it at an angle? Is there a big rock coming up? So despite it being so long, you're constantly engaged, which is also crazy, because you know, there's only eight of us, and we did very little talking for 10 hours. And maybe as you can tell, I'm a very social person. And I enjoy like talking. So it really is, you know, for a 10 hour event, it flies by really quickly.

Andrew Vontz 18:03

And there's been a lot of I don't know, if I would say controversy, there's been a lot of discussion about the text messaging that was going down among the writers in your group. Were you all just sending each other selfies or what was happening?

Ian Boswell 18:15

I did not send any text messages during the event. My cell phones a bit old now. And my battery died way too quickly. Nokia brick, yeah. Nobody. And I knew Keegan and Russell were gonna do this ahead of time. They, they did it last year as well. And you know, one of the hundreds of It's a rule, but one of the, I guess, maybe there's a rule of unbounded you're supposed to carry a phone, you know, I guess it pertains to the elite riders, but you think how many people especially this year, you know, broke something had a flat tire at some point, and, you know, there's no follow up or you need to get back to Emporia somehow. So having a phone is, you know, very needed in most situations and for, you know, almost every writer. So what they were doing is they were essentially just texting ahead to the aid stations, saying, you know, every writer has a plan, you know, by coming to the aid station, I'm gonna get, you know, two bottles, a hydration pack and whatever, some gels or bars or, you know, some people pizza and a hamburger. So, they were just texting the head to the mechanics saying, like, Hey, this is what I need, which is it's completely within you know, I guess the the rules of the race considering you have to have a phone. It doesn't bother me because I could do that just as well. If I wanted to, I could carry a phone and you know, make a phone call. One thing that they both also had was headphones, they don't have, you know, headphones like I'm wearing but they have those, I don't even know if they're called shocks or something. They're like those Yeah, vibrating headphones. Right. So they were listening to music, which again, I think is tons of people do that out on course. I am finding that becoming more dangerous now, though, especially less for the elite group. But as we start to catch 100 mile finishers and we're saying hey, we're on your left, and you know, someone's listening to a podcast or listen to music and they don't hear us coming up. And that's dangerous for them and for us, because you know, maybe the last minute they swore right or left, even though we're trying to make noise to let them know where we're coming. But again, for some people, if you're out there by yourself for, you know, the 100 mile course, or the 200 mile course, I would definitely want music and I was by myself. So I don't know what the best, best thing for them to do there as but as far as the cell phones go, I think it's I mean, I don't have a problem with it. I think if I had a choice, and I will make this recommendation to the unbound staff, I think it'd be really cool. If for the elite category, the aid stations were self supported. So not you couldn't have outside staff. So I did Cape epic this spring, which is a eight day mountain bike race. I wasn't in the pro category. So you know, we just filled up our own bottles and stuff. But the elite riders can have a mechanic come and set up their station, they can put a box there with, you know, spare wheels, and tires and derailleurs and chains, everything that they need there, but they can't receive assistance. And I think that would be a really cool addition to the unbound Elite Field especially because we do have separate starts now. Where if you come into the aid station, you can have your mechanic or friend or husband or wife set up a table and put lay out all your stuff as you want. But you can't have someone come and help you change a tire put up hydration pack on because we were really fortunate this year that it was such a small group at the first aid station. Because you know, people are now doing you know, they'll dump their hydration pack as they come in, they'll grab one halfway down, they'll maybe stop, maybe not, which works if there's a riders, but if we came into that aid station with 70 people, it's going to be mayhem, with people trying to grab packs in the side of the road and dropping stuff. But if it was self, from self supported, I think it would just add another element to gravel, which I think is cool. But you have to know your own bike, you have to know how to fix it. If you want to hose it off. You can someone can set it up for you, but you have to do it yourself. There's also to limit the level of entry and I saw some videos afterwards of people coming into the aid station that had five people. You know, someone grabs the bike, someone does the bottle, someone does the chain. I'm like, I had two guys from Oahu, who you know, they're not mechanics there. They work with me at Wahoo fitness and they just literally I'm like, we're just gonna keep this as simple as we can. I'm just gonna take hammy, my bottles and my hydration pack. And that's it. And then I'm gonna keep riding. Like that's all I did at the aid stations. I think the last one I was it was like three seconds of stoppage time. And, you know, I think that's like a choice that you want to make. If it's if you don't have, you know, if you need to bring five people there with you, you know, you're looking at several $1,000 for flights, lodging rental cars, which is it favors the people who are in teams and athletes that have that level of support. And it really limits people, especially we're coming from Europe, you know, and it's already super expensive to take a trip over. And all of a sudden you realize, oh, I also need five people to you know, do a Formula One pitstop on my bike. I think it would add a little bit more adventure to that race as well, if you had, you know, self supported, but I have a lot of opinions on things. And I think sometimes people don't always agree with what I have to say or how I think about it.

Andrew Vontz 23:18

Well, and I'd love to hear more of those opinions. And I'm grateful that you're here today to share them. I watching the videos from different writers who did post race recaps I of course, I caught Kerry Warner's video of the mud section. And I'm hoping to get Kerry on here soon. Big fan of his work. But looking at the pitstops, right? I mean, it is at an f1 level. Now it's bananas. Right? You got people to mechanics on one side, two mechanics on the other side, the bottles, the packs, hydration, food, everything. Another thing that stuck out to me. And when I saw photos of the finish, I was wondering if I was looking at Photoshopped images, you were actually there. So I want to ask you directly. It looked like you had a lot of writers who probably were doing the 150 or 25 in the shoot while you had seven world class athletes trying to sprint for the finish. Is that actually what went down? And what was that like?

Ian Boswell 24:16

Yeah, and that's exactly what happened. I mean, it's happened the last two years I guess I can't actually recall in 2021 If Lawrence and I had anyone else in the shoot. Let me clear when I looked at the photos Yeah, but we did have we did have some people in the foot in the chute last year when it was a sprint have four of us or five of us. I mean, it is crazy. I saw like I saw a video as well when you're when you're in it you don't see it. You know like you don't you're just like you see your line and you're like cool. I'm this is my line. Like everything else is kind of a blur. But looking at a video I was like there was some guy you know, in front of Keegan like taking a selfie. You know, this is his year long, challenging goal to come here and write about he's crossing the finish line taking a picture as you know, Keegan's sprint in it, whatever 12 100 watts. It is, it is dangerous. I mean, I think, you know, the event is fortunate that nothing has happened. I also do foresee going forward, unless there's, I mean, maybe the northern course I'm not sure when you did Unbound, it's a little bit more, there's some hills later in the race, so it could actually break it up. But just having observed the race, the last two years, everyone is so fatigued, even the elite riders, you know, everyone is the top, you know, your 10% of your acceleration is just gone. So you can attack, you know, people made attacks in the final, you know, 510 miles, but you can't maintain it, you know, so you attack and then you're kind of off the front, you kind of just get sucked back into the group of riders chasing. And I think that's going to continue to happen unless, you know, pug or Char welven, or, you know, someone who's someone who's just on a completely different level, but of the riders who are there. Now, the difference between us is so small, you really can't get away in the final, there's no, you know, the running back into employee, it's pretty smooth, it's relatively flat, you're so fatigued that you can attack but you can't maintain, you know, that attack long enough to where you're going to get a gap. So I mean, I mean, honestly, I think that for the next, you know, who knows, maybe indefinitely or until there's a muddy section later on in the race that you are going to see a bunch finish. And something I mean, probably needs to be done, I don't really know what to do, because I guess I also really value the people that this is their, this is just as much as their event it is it is the elite event, you know, so you can't tell them to stop. And here's my daughter coming in. You can't also you can't hold them, you know, at the at the university and say, Hey, you guys need to stop here. Because the elite riders are coming in, you can't prioritize their events over our event, you could potentially do two shoots, where it's like, hey, the elite riders are coming in, they're going to, you know, shoot up the left side here. But even that, I know that there's some concern, and I guess being on the fire department here and PJM they need those lanes on the side in case there is a fire scene. So they have to have they can only close down one. They can't close down the whole the whole road. Yeah, you have a baby. Yeah. But yeah, I really don't know what they're going to do for that. Yeah, thank you. You want to say hi?

Yeah, it really is, like a concern that they're gonna have. And I think, you know, I mentioned to someone a lifetime of possibly splitting the days, you know, doing the, you know, open category, the, you know, the 50, the 100, you know, the master 200 event on Saturday. And then on Sunday during the elite event that would also give the women their own race where they're not going to be caught by the men. It would give everyone else an opportunity to, especially if they can really nail in the the live coverage where they have a jumbotron downtown, and everyone gets to sit downtown and watch the elite riders race, you know, they just I hear they're coming up to this section. If you remember this from yesterday, that would be really cool. But I know logistically closing down a town for two days becomes a huge inconvenience.

Andrew Vontz 28:17

Do you have any interest in racing the I don't even know what they're called. But the UCI World Tour level of gravel events. Does that have any appeal? Do?

Ian Boswell 28:25

No, not to me. Which is you know, I guess I'm I'm in a, obviously a unique position. I guess I came to gravel with a different very different perspective than I guess a lot of my competitors. You know, I never expected my gravel career to be a career. You know, I left the world tour in 20, end of 2019 2020. Right, very much retired, you know, and I still love riding my bike. And then the pandemic happened and I stopped training and just like really fell in love with riding my bike and exploring. But you know, with my job at law, who I knew I was going to be at events, you know, and slowly I kind of got fit again, just because I loved riding fast and it's fun to test yourself. And, you know, my trip most of my training to be honest, is going after my own Strava kom is around my house here and impeach me. No, it's, you know, most of my efforts are just like, Hey, can I go faster up this climb that I did last year, two weeks ago. So I guess I still want to keep it fun. And I for me road cycling, gravel cycling, it's still fun for me to go fast. But to sign up for, you know, the lifetime Grand Prix series or the UCI stuff, it's, I kind of am worried if I do stuff like that. It's kind of like stepping back into what I left behind. You know, where it's like you're racing for results. You're chasing points. You're trying to get a contract. You're trying to get new sponsors. It's different in many ways, but at the same time, I feel like that chapter of my life is kind of I got to experience that I feel very fortunate. And I'm glad that there are those opportunities for young athletes now, especially in North America because road racing has almost disappeared. But they have the opportunity to chase a career and make a career in and you know, gravel mountain bike, you know, kind of this mixed surface racing. But for me, it's no, I told myself before this year Unbound, like, cool, this is my last year racing bikes, like I'm done with it, like, I'm gonna go to unbound one more time, and that'll be it. Okay, I finished fifth again, it's like, okay, well, maybe I could do another year of it. I don't know. And maybe it's not. And, you know, I still love you know, I've had the opportunity this year to go to a bunch of smaller events in different areas. One out in Oregon, where I grew up, I went down to event in Mississippi, Cape epic events that I otherwise wouldn't have done. And I guess if I added, you know, the lifetime Grand Prix or the UCI events to my calendar, you know, I only have so many trips in a year just with, you know, family and job and, you know, our house here, that those would be taken away trips that I have events that I really want to go to, you know, events, I would love to do an event in South America, I'd love to go back to Japan for you know, in some capacity, whether it's a bike race, or notice or grinduro event over there. You know, unbound is kind of like the event that you kind of need to go to, it's the crown jewel. But yeah, as far as the UCI stuff, I mean, I think it's, it's just at this point in my life, it's not my cup of tea, I don't feel like I need to prove anything. In gravel racing, which I mean, sounds weird, because I'm still competitive at, you know, the events I go to. But I also, I also feel, and I've had, you know, this thought for a while, like we've had, and we still have the opportunity to measure gravel differently. You know, do we really, in my opinion, like I said, most people disagree with this, who are young and up and coming and I see why they want a world champion. Like why do we need the best? Why do we need to have a world champion? Why can't we have Keegan's kind of also wreck this because he just wins every race in North America. But why can't we have Hey, you are the best on this day at BWI, and you are the best on this day at unbound and you are the best at you know, gravel worlds in Nebraska. Maybe it's just more of a thought of like, I think it's really cool when that success can be shared. And even sometimes success doesn't have to be winning, you know, it can be, you know, how people are writing in the group and how people you know, Ted King at gravel locos, you know, stop to help pace and after he had his concussion like, can that not be the win? I guess it's, I have a different very perspective, a different perspective now than I had when I was, you know, 25 years old. And all that mattered was trying to win and try to be the best. At this point, I'm I see that there's a lot more value to a broad range of kinds of accomplishments. And I hope and I see gravel is recognizing that. But we do still have the opportunity to measure success differently than just having the best rider or the world champion. I feel like there's so many more levels and depth, the best that we could find, then just the first question that crossed the line.

Andrew Vontz 33:08

What do you get out of participating in these events, because as you noted, when you left the world tour, and I'd love to dig into that and talk about it a little bit more, which we can get to in a minute. But, you know, unbound is not a short event. And even if you're just running, you know, riding around chasing KLM I have to imagine you're putting a pretty substantial amount of time into training you have a family you have a job. Do you consider yourself retired still, at this point from competitive cycling?

Ian Boswell 33:37

A tricky question, I would say no, because I still do put a lot of time I still do put a lot of time. And I guess I've kind of shot myself in the foot with that one by being competitive. You know, like I could have just like, hey, I'm just gonna like go to these events and right easy. But it's still for me, it's really fun to ride fast and I guess I do know that that won't be the case forever. A couple of weeks prior to unbound two friends came and met me in my house and in PJM one came up from Upper Valley in New Hampshire and one came down from Quebec and we did this they both wanted to do this unbound training ride so I mapped out 120 mile loop and it was you know, 13,000 feet of climbing which is a ride I never really do by myself. Even in the years past I've never done ride that big getting ready for for unbound you know turned into seven and a half hours and you know, we rode it pretty much the same pace we ride unbound at and I realized there that I got the same sort of satisfaction of that ride as I do from unbound you know riding really hard and really long with really strong people and I that's one thing living in Vermont that I don't get a lot of you know, there's not there's cyclists here but there's not a lot of racing cyclist or there's not a lot of people who want to ride at my speed for five hours, you know, and so sometimes for me it's going to unbound or going to SPT or events that I get to I experienced that, you know, and I and I just something I don't get at home. And you know what it's like being an athlete. It's that it's those endorphins. It's that feeling of okay, I did it, I accomplished it. You know, I'm maybe like, some most people out there who do endurance sports, I'm so much more productive after doing a long, hard ride than I am before, which makes no sense. You know that I can go thrash myself and I come back and I'm, I'm in a better headspace. I'm thinking more clearly happier. So yeah, I mean, I still put in the effort. And obviously the the work that it requires to do, unbound. At the same time, though, I look at, you know, what everyone else is doing. I'm like, Oh, wow, I must have like this imposter syndrome, like, looking at Keegan and Russell train for unbound on Tucson before the race. And like, I can't keep up with those guys. I don't have 30 hours a week or 25 hours a week to ride my bike. So I guess I do what I can. And you know, fortunate in the sense that I do have a history in the past of racing at a high level. So you have those miles in your legs, you have that knowledge, you kind of have that depth. So I'm fortunate that probably I can get to that level with less effort, not less effort with less training time. But just maximizing the time that I do have. Do you have a bit of bass? Yes, I've got a couple of years in my legs. At this point. Yeah, I've had a

Andrew Vontz 36:22

few few years in your legs when you pull up. So when you think about your time in the world tour, what did you enjoy about those years? And is there anything from that experience that you're getting out of what you're doing now?

Ian Boswell 36:36

I mean, I'm sure there's probably shifts all the time of what I enjoyed about it. And I guess now in reflection, you know, my friend Larry wore bass was over for Unbound, you know, he's still racing the world tour on a GTR. I guess what I enjoy about it now is that I achieved what I wanted to as a kid, you know, I mean, it sounds strange when I speak to my friends, because a lot of them are elite cyclists. And you know, we all made it, we're friends, because we're all racing in the world tour, we have the Grand Tours together. So when I take a step back and realize that, you know, I grew up on the West Coast of the US that's really far from Europe. And you know, watching the Tour de France on TV as a 1011 12 year old, and thinking, hey, I want to go there one day, and I want to do that. And to realize that I got there and I achieved that, did I win the Tour de France? No, I mean, the closer I got to the top, I realized the top is further away than it is from going from Oregon to the World Tour is from where I finished in the tour to the to the top. But I think that's what I miss most is it was like a childhood dream that I got to live that life, I got to, you know, live in Europe for a year. So I got to race with the best athletes in the world on the, you know, the biggest teams on the best equipment. I don't miss really anything, I guess it's more admiration for what I did achieve, you know, and kind of the work that went into them, the people that supported me to get there, you know, my family and the sacrifices that I made that paid off, you know, because I feel like we all make sacrifices to try to achieve something and sometimes it doesn't work out and the fact that I, you know, whether it was the right place, right time, but I was, you know, started somewhere and I got to where I wanted to go and I think it's more kind of being proud of of what I achieved and accomplished and where I got to over. I mean, of course I miss having a team chef and you know, having someone do my laundry on a grand tour and you know, getting a massage when you want but those are all those are all kind of superficial things. You know, you can go out to a restaurant, you can probably impeach him, you probably couldn't find someone to do your laundry, but those are all things that you know, they're luxuries, but they're not necessarily things that I miss, you know, and I guess that's why I've kind of come to love gravel is because I also do enjoy looking after myself. You know, I have enjoyed learning how to work on my own bike and learning about the equipment and, you know, technique and all that kind of stuff.

Andrew Vontz 38:56

When you were a little kid like before these years when you kind of became fascinated by the Tour de France and had this dream of going to the World Tour. What were you into and what were you like

Ian Boswell 40:06

I mean, as a kid, both me and my, my younger brother were always into, into sports. I mean, whether it was I played basketball, I played football, we did track and field we, you know, we would do fishing, hiking, backpacking, cycling, my dad was a triathlete in the in the 80s. My mom did some mountain bike stuff in Oregon, so the bike was kind of always there. And it was always like a, you know, from the minute I could first learn how to ride it was also like a mode of transportation in the mode of freedom, you know, to go ride down to my friend's house or to ride to school. It was like a sense of independence. You know, when I was goodness, maybe eight or nine, you hit a little like the road I grew up on a bend Mila couture Saginaw, my dad had an old yellow, winning Jersey magazine, yellow jersey, that we would race to the park and back, and we had, you know, five stages around different, you know, courses a time trial and a bunch sprint. And so as I was aware of cycling at a pretty young age, you know, especially for an American kid in the, in the 90s. But there was always, we were just always active, you know, that's something that's kind of always been a common thread through my life is physical, you know, physical exercise, you know, just being outdoors and, you know, whether it's playing or whether it's, you know, competition doing stuff outside.

Andrew Vontz 41:47

And when you got to the world tour, and I know that you've left the world tour because of things related to concussion, TBI. But prior to that, were there any moments when you felt like, I don't actually know if I can cut it? Or did you always have a high level of confidence and you just carried it through?

Ian Boswell 42:06

I would say I've always had a pretty low level of confidence. You know, when I first signed with Team Sky and 2020 12 I sign first season was 2013. You know, I signed a three year contract at the time, which is a really long contract. In those days for a young rider who, you know, had raced in Europe, I'd never lived in Europe. And I remember drafting, like a couple of emails to Dave Brailsford, who was the team principal, British term for like Team Manager. Like drafting emails of like, you know, what, like, I don't deserve to be on this team, you should give this thought to someone else, just because I wasn't performing. You know, I guess I knew. I mean, I was also, you know, 21 years old, and I was on the best team in the world. You know, we went to every race we went to, we were winning, we had, you know, the best riders, they just won the Tour de France the year before they won the Tour, I think every year that I was at the team almost. So there was a level of, you know, kind of lacking self confidence just being surrounded by greatness from such a early age in the world tour. But, I mean, I guess I just kind of kept working, you know, I never sent that email, thankfully. So I kept kept my job. But I think I was also going through a lot at the time, you know, I was 2021 22 I was living in Europe, I was trying to learn how to live life in a foreign country while simultaneously trained with with the best athletes in the world. So I think that really took a lot of additional energy just to survive while trying to trying to train you know, getting a phone.

You know, when I was in Europe at ages 2122 And I was, you know, instantly surrounded by the best athletes in the world and I wasn't, I wasn't performing to the team's expectations or my expectations. And you know, as I was trying to learn how to train like a world tour rider, I was also trying to get a life set up in a foreign country without speaking French very well without having You know, family around or, you know, I had friends, but they're also within cycling, you know, so if they were doing well, I was like, Oh, I don't want to hang out them because I'm, you know, I'm kind of struggling. So I'll just like, kind of stay by myself and, you know, try to figure out, well, how do I get a cell phone? Where do I, how do I go about getting a French driver's license or a visa to live in the country, you know, so I was immediate, immediately thrown into this world of the best athletes in the world who are performing every weekend week out at the races while trying to set up a life. And, you know, I, you know, thankfully, like I said, had three years on the contract. And before the final year of that contract at Sky, you know, I kind of had finally figured out all the stuff off the bike, you know, I'd become settled and comfortable in France, I learned how to, you know, to train at that level, my body had kind of caught up with, you know, I guess, my lifestyle and then started to perform, and then I kind of like, cool, and now I actually, you know, kind of belong here. But, I mean, I had the same lack of confidence, even this year at the start line of Unbound, like, why am I getting a call up, you know, because I was there last year, like, this is weird, I see all these people in the amount of time and energy they, you know, they've had for training and, and like, all their support staff, and I was like, I don't have all this, you know, I've got great sponsors and partners, but I also don't want five people there, you know, spending their weekend to look after me because, you know, unbalanced kind of a crapshoot, you could flat in the first 10 minutes, and then you have five people waiting at the aid station for you never showing up. But I also think I don't really, I guess I do a good job or a bad job of not putting pressure on myself in that regard of you know, not over promising things. Performance wise, because I know, sport can be incredibly, you know, unpredictable.

Andrew Vontz 46:47

When those feelings showed up for you on Team Sky, how did you deal with them?

Ian Boswell 46:54

I mean, I remember a lot of like, doing really funny thing, you know, at the time, it was before GPS by computers, you know, so we had an old SRM and, you know, you're supposed to upload your, you know, now when you finish a ride, you know, especially with my wall, I finish I get home, I say, but it's sent to my training peaks and sent to my Strava sent to, you know, the Wahoo app, like there's no hiding, like you did, right, everyone knows about it. In those days, you know, you had a plug in your SRM to your computer, download it, you know, send it. And there were times when I would like, you know, upload the file, I didn't do the training, I was supposed to, you know, had a coach who was telling me what to do. And I would like delete the file. Because I was I was like, Oh, my SRM just didn't work today, because I didn't do the ride, or I didn't feel good. You know, fully knowing that, like, there was an expectation of me to do the training, I didn't feel good, I didn't feel confident enough to also tell the team or the coach, okay, I'm, I'm not feeling well, or I'm just this isn't working out. So there were those circumstances when I just completely kind of, yeah, pulled the wool over their eyes, but it wasn't for lack of trying just things weren't, things weren't working out. And I think I was really struggling, just to like, feel, you know, comfortable in Europe living there during the training, because it was a huge training load as well, back in 2013 1920 year olds, were not doing 20 plus hour training weeks, and, you know, training like World Tour riders at a young age, which now they are, you know, now, coaches are tracking your sleep, your blood glucose, your training, you know, they're tracking everything, and there's really no hiding, you know, what you're up to? But, you know, just 10 years ago, you could kind of like, oh, yeah, I did the train ride, but it just something happened in the file. No, okay, whatever, like, you know, get back to it tomorrow. I think my thought was, I mean, it's hard to go back. And and think about that, but you know, I guess I did. I never pulled the plug, you know, I stayed in Europe, I kept doing the training, you know, you have ebbs and flows, and I kind of gradually, like, you know, maybe it's two steps forward, one step back, eventually, I got to the point where, you know, I started getting selected for bigger races, I was, you know, feeling more part of the team, like I was a valuable member of the team, rather than this is just that young American guy who showed a lot of promise but hasn't really delivered, I finally started to kind of find my way in the sport and, you know, gain that conference, which was, it was a good reminder as well, that, like, I was in a very fortunate position to be where I was, because at the time, there was a lot of kids who would have given anything to be in my position, and so to also recognize that, you know, that sentiment as well that I was, you know, I was where I wanted to be, and I had done the things to deserve to be there. But now's the time to kind of show that you know, and I think that was one of the biggest mistakes I made when I joined the World Tour was for so long. You know, you have you have annual goals, you have, you know, monthly goals, I want to do this race, I want to train this much I want to be, you know, underlying all of that from the age of, you know, 10 or 12 Was I want to make it to the biggest team in the world. I want to be on the best team. And the minute I signed a contract for the team I had checked off a huge goal in my life, you know, I had I had met this goal that kind of an underlying everything up to that point. And when I got there, I didn't reassess, okay, well, what's my next goal? It was kind of like, sweet, I'm here, I made it, I just signed a three year contract with the biggest team in cycling. But I never set goals from there, you know, going forward from there, because all of a sudden, I was on a big team, and you kind of assume, Oh, they'll set goals for me. And they, you know, they'll look after me. But I never did that myself. And so my third year, a Team Sky. I met with a friend who was a nice and older gentleman who was an American, but worked for a French company. And he was, you know, MIT ran a business. And he's like, Ian, where your where's your business plan, I'm like, I don't have a business plan. I'm just at this team. And, and looking in hindsight, I had done that throughout my whole career, then I got to the world tour, and I stopped setting goals. And so throughout that winter, after my first two years of sky, I kind of threw out the baby with the bathwater, and reset everything, you know, I was like, Cool, I'm gonna set a specific goal of, you know, things that I have direct control over, like, here's how much time I'm going to train, here's, you know, how much time I'm gonna spend on my time trial bike, or I'm going to spend, you know, studying race footage. But then I also set goals that I wanted to achieve, but that the team had more control of, you know, I wanted to do a grand tour, I wanted to be, you know, top 15 In a world tour time trial, I wanted to be, you know, one of the last mountain domestiques. And like, as much time as I put into that, during the season, I never really looked at it. But it is amazing how have you set these goals at some point, and you just like, you've written them down, they're subconsciously in there. And slowly, you start to chase them and tick them off, you know, even without, like, you know, I wasn't annually going through, you know, every quarter going through, oh, how am I stacking up against my goals. But I had set these goals. And slowly, I was like, achieving them, which is what I did, throughout my young career, to get to the world tour, I started doing that on the world tour to, you know, achieve the goals of, you know, riding the grand tour, or being top three on a stage or riding the Tour de France, it all started to happen, because I had, you know, kind of just reinstalled this idea of like, goal setting is really important.

Andrew Vontz 52:11

Were you able to share about the experience that you were having, particularly as it relates to kind of self confidence in your own identity with your teammates at the time? Or did you feel hyper competitive with your peers?

Ian Boswell 52:27

There were teammates that I mean, fortunate at the time, there were some other young riders at Team Sky, there was an individual Nathan Earl, who was Tasmanian and we were kind of both in the same boat, like we had the races we would sometimes do, okay, oftentimes wouldn't really perform. So we like really bonded, you know, we were trained together, we go out to dinners together, we'd spent a lot of time together. But we would kind of avoid, you know, because I lived in nice France, which is, you know, just next door to more or less next door to Monaco, which is where all the stars live, you know, Richie Porte and Chris Froome, and Joe bear and all the guarantano is all the, you know, the big, big wigs on the team. So we wouldn't see them. But, you know, we knew that, that, you know, they were kind of on another level of, you know, they were, they were the best riders in the world. And then I guess, also by not hanging out with them as much, you're also not comparing yourself to them constantly. I guess that's kind of like, a huge reminder that I learned through this. And when I said earlier about, you know, what I miss about the World Tour is that, you know, I was comparing myself against legends of the sport. You know, I wasn't comparing myself to the kids I grew up racing with, you know, what I had accomplished compared to what they accomplished. I was comparing myself with oh, well, Froome, who just won the dolphin to Richie Porte just won Catalonia it's like, that's a pretty, those are pretty good athletes to compare yourself to, like, you may never achieve what they half of what they achieved. So I think kind of resetting, what I was measuring myself against and measuring myself against myself, rather than measuring myself against the world tour rider. So I think there was a moment there where Yeah, I would tend to hang out with kind of riders on the team who were more along my, my level and my caliper rider.

When your

Andrew Vontz 54:26

world tour career reached its end. I'm guessing that's not the way that you anticipated that you would leave the world tour. So what happened and how did you feel about it?

Ian Boswell 54:36

Yeah, so I had a crash in the spring of 2019. At the Torino Adriatico I had a crash don't really know how it happened. But I went over the front of the handlebars and suffered a concussion like a TBI. You know, and I had had a number of crashes and concussions throughout my career. But this one was different. You know, the Recovery was a lot longer and you know, I was I guess 28 At the time, I think 28 You know, and in many ways, like kind of, you know, I guess cyclins change in the last five years, but, you know, at the time was kind of coming into the prime of my career as far as being a grand tour rider, you know, not to win, but to be a, you know, a Domestique for, you know, the team's leader. You know, and at the time, there was a crash, cool, you're gonna take a week off, you'll come back, and you know, you'll ride to our California and then you'll ride the Tour. And in July, that was very much so my plan. But the longer the recovery took, the more time I spent away from the sport. And I'd actually come back to Vermont for the first time outside of an offseason, ever, you know, I from when I signed my contract and 21st season in 2013, I pretty much lived in Europe full time, you know, I would come back, oftentimes, you know, for maybe a month or two in the winter, but that's offseason, you're not training for months, also a terrible place to try to train for professional cyclist in November, December. So I actually came back in the spring, and, you know, I guess it that time, I didn't race the rest of the season, you know, so from March, March or April 2019, I, I, you know, there's a couple of times I thought I was going to come back, but just the the lingering symptoms from the crash, and, you know, the, the recovery and everything, just, it wasn't feasible to come back that year. And so during that time, you know, I kind of started to have some of these thoughts of like, well, I actually accomplished a lot in my career. And also, the previous year, Garrett Thomas had won the Tour, you know, not only unexpectedly because he's really, you know, kind of become one of the, you know, favorites of any grand jury goes to, but somewhat, you know, unexpectedly won the Tour de France ahead of, you know, do Milan and Chris Froome. And I told them, when we wrote into Paris, I was like, Dude, you should just end your career now. Like, you're on the shortlist say, take the yellow jersey, make well, like a thank you speech and just mic drop and, and get out of here. And I realized, through that process of recovery, that like, there's never an end for, for an athlete, you know, and this is one thing that kind of still puzzles me, you know, even, you know, why did I go back to unbound the last few years? I don't know, because you when something wants to say, Oh, can you win it again? You know, Oh, can you win five Tour de France? Can you win the Giro and then the Tour de France? Or can you win unbounded, then Leadville, you know, it's just like, there's never an end to it. And I guess that's what I realized is like, you know, I had accomplished a lot. By the age of 28, you know, I had written the Tour de France, I'd written the Vuelta three times, I'd written the Giro, I, you know, spent eight years living in Europe as a, you know, you know, a young man, which is like, how cool is that, to be able to live in Europe full time, you know, fully integrate into a culture and speak the language and, you know, cook the cuisine and travel the world. I also my wife, and I got married that year. And I realized, like, you know, what, like, what am I chasing? You know, like, what, you know, cool, maybe if I stayed in the world for another five years, I could, you know, maybe I could win a stage in the Tour, or I could, you know, sign a bigger contract. But ultimately, you're always chasing something. And I guess that was the moment when I stopped chasing and started to like, embrace what I had, you know, what I had done what I was doing. And also the concussion paid, played a big factor. And, you know, obviously, I'm still racing my bike today. For me, gravels much safer, because I can kind of assess the risk that I want to take. But I'm pro road racing, it was also a case of, you know, it's not a matter of if I crash again, it's when, you know, if you're on a wet descent in the Dolomites, like, you can't just let the wheel go and be like, Oh, close it, when I get to the bottom, like, you're not going to close that gap in gravel. You know, as I kind of said, through the mud, I can let the guys go up the road. And the speed is low enough that I Well, if I, if I'm strong enough, I'll close the gap. If I can't close it, I can't close it. But I'm not going to race down this descent, to try to keep these you know, keep on these guys wheel because I just don't want to crash and I can't call my wife from a hospital again, like, Hey, honey, I hit my head again, I've suffered another concussion. So a lot changed in that time. And I think, you know, a lot of athletes if they ever had a forced sabbatical, I think they would kind of approach things differently. And I definitely did. But yeah, I mean, I like I said, I still love the sport, I still admire, you know, what those writers are doing. And in the world tour, I don't want to do it again. You know, if a team came and offered me, you know, a huge contract to go back and race I'd be like, You know what, I've, I've ticked that box, I feel super fortunate that I have that chance to race those races and live that lifestyle, but I'm a different person now than I was, you know, and in to that from 2013 to 2019.

Andrew Vontz 59:52

And you mentioned during that third year at Sky when you had your friend who ran a business you kind of started to set some new goals for yourself. I have a new business plan for your life and your professional life, so to speak. When you think about today and what you're doing now, with your family, with your professional life at Wahoo, with you as a bike racer, what do you want to be getting out of all the different things that you're doing?

Ian Boswell 1:00:16

Yeah, I've really thrown a wrench in my own spokes by doing well in, in bike racing. Again, as much as you know, it's I and I don't want this to come across as like cocky or arrogant, but like it's almost this, it's almost a curse that I'm doing as well as I am. Because if I went to unbound this year, and I just got my butt kicked, the writing's on the wall, you know what I'm gonna hang up my wheels, I'm gonna come back to Vermont. And I'm just going to spend time with my family and, you know, work on our little homestead. But I'm still performing. And as much as I love that, it's also like, like, I still have it in me, I still am able to do it. And so I guess my my internal question, now, you know, after this year is unbound is just because I can do it, does that mean I should do it? And that's something I really am struggling with, you know, because, like I said, you know, I told my wife, Hey, honey, this is my last year racing. Next year, I'll be home more, you know, I won't spend as much time riding my bike on the weekends, I'll help you with, you know, you know, more things around the house, we, you know, we live in an old farmhouse, there's an endless list of things to do, and the endless, like, you know, list of skills that I need to learn and want to learn. And every year I continue racing, I feel like I'm just kicking the ball down the field, like, oh, you know, I'll just do it next year. I'll fix that next year. Well, it's been, you know, three years now of me playing in gravel. But I do know that at some point, there will be an end because you know, I'm not going to, you know, I can't be fast forever. I still do love riding my bike. So I guess for me at this point, it's more of if I were to stop when I miss it, or, you know, or could I have that clean cut like I had with professional road racing was like, You know what this is out of my system. Now, I'm ready to do something new and different. But I guess the biggest difference is, I've been much more successful oddly, in gravel racing, when I was in road racing. Trying less hard, if that, I would say, trying less hard, but like, I'm not, I'm living a much more balanced life. And I was in the world tour. And I think, ironically, had I done this in the world tour, I would have been more successful. You know, the, it's funny how, like, with age, you learn so much and like you change your, your values and your perspectives and kind of, you know, the balance in which you go about your day. And you take some of that pressure off, you know, when I was 25 years old, living in France by myself, racing the world, where that's all I was thinking about, you know, everything was just about this singular mission of being the best writer, you can now it's, you know, as you saw, you know, on this podcast, my daughters, and I just heard the smoke alarm go off, you know, I'm on the fire department get calls at two in the morning to go, you know, help someone who's lost in the snow, all these other things that are distractions from the thing I love most riding my bike. But things that probably enhance me riding my bike, because they take your mind off of, you know, that pursuit, you know, it adds a level of like appreciation, when I do get the free time to go out on my bike ride. And my phone's not ringing or, you know, our daughter's, you know, taking a nap and like how cool I can go out and do two or three hours and come back and like, I don't feel like that was a pleasure to get out and ride. It wasn't like a job to get out and ride.

Andrew Vontz 1:03:35

Do you still sweat recovery? Because just when I hear the mix of things you've just described, you're getting the call in the middle of the night for the volunteer fire department, potentially, I don't know how your daughter sleeps, I have small kids, there are rumors that sometimes they disrupt your sleep. So you might not be getting that World Tour level recovery? Or are you? Is that still something that's super important in your order of operations?

Ian Boswell 1:04:00

No, my recovery now is pretty horrible. You know, our daughter was up last night from midnight to 3am with who knows her teeth are coming in or she had a nightmare. I don't know what it was. But you know, my I couldn't have in I don't know how people in the world to have a kid because your recovery is so important. And of course it is important now. But I'm not putting in the same training load that I was in the world tour, you know, I'm more preparing for one day events versus you know, three week events. So I think that is important as the recovery is I can get by with maybe not focusing as much on on recovery. And I think for me, just being kind of a busy mind. I think sometimes having those other those other distractions is actually helpful, you know, to have all these other things going on in my life. As much of a distraction I know as it is to my sport and also brings me a lot of value and kind of joy and pleasure outside of the bike. And that's kind of where In this whole, you know, struggle comes with having other opportunities away from the bike, I know that if I stopped racing, there's so many other things I can put that time towards. But they're things that I'm not as proficient in, or I'm not as you know, I don't know the the outcome of those things, you know, fixing our barn roof, it's like, I know what needs to be done. I know I could learn it. But that means like, cool, I'm going to spend, you know, three weeks in the summer not riding my bike, and every free moment up on a ladder on the roof, you know, taking, you know, 10 off the roof and patching it, which is something I want to do. But at the moment cycling's kind of like the easy escape, like, Oh, I'm good at this, I'm just gonna stay in this lane, because the roofs pretty high. And it's a pretty old barn and I don't want to fall through it. So it's easy. It's easy for me at this point in my life to stay in this lane. As much as I also want to change change lanes and try something different.

Andrew Vontz 1:05:55

mean, who knows, and you could very well become the next 10 roof barn influencer. I mean, I'm sure that's a nice waiting to be filled. We didn't even get to talk today about, you know, your experience and your depth and podcasting, but I'd love to have you back in the future to dig in on that. Because, you know, storytelling is a big part of your DNA as well. But I want to thank you for being here today and for sharing about your journey. This has been awesome.

Ian Boswell 1:06:24

Yeah, absolutely. And I'm seeing at the top of my screen says Choose the hard way. And I think that's one thing that I will say in closing that there is no substitution for hard work. You know, I get asked all the time, how do you make it to the world tour? It's like, there really is there are shortcuts people take they always come back and bite him and he asked me and like there is no substitution for like, putting your head down and just getting it done. Whether that's business sport, you know, parenthood. Sometimes you can't go over it can't go through, you know, around each have to go through and you you really do have to go through that hardship to get to where you want to where you want to end up